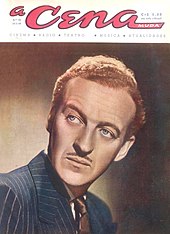

David Niven

David Niven | |

|---|---|

David Niven in 1973 | |

| Born | James David Graham Niven 1 March 1910 Victoria, London, England |

| Died | 29 July 1983 (aged 73) Château-d'Œx, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Château-d'Œx Cemetery |

| Education | |

| Alma mater | Royal Military College, Sandhurst |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1932–1983 |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 4, including David Jr. |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service | British Army |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel |

| Service number | 44959 |

| Unit | |

| Battles / wars | Second World War |

| Awards | |

James David Graham Niven (/ˈnɪvən/; 1 March 1910 – 29 July 1983[1][2]) was a British actor, soldier, raconteur, memoirist and novelist. Niven was known as a handsome and debonair leading man in Classic Hollywood films. He received an Academy Award and a Golden Globe Award.

Born in central London to an upper-middle-class family, Niven attended Heatherdown Preparatory School and Stowe School before gaining a place at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. After Sandhurst, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Highland Light Infantry. Upon developing an interest in acting, he found a role as an extra in the British film There Goes the Bride (1932). Bored with the peacetime army, he resigned his commission in 1933, relocated to New York, then travelled to Hollywood. There, he hired an agent and had several small parts in films through 1935, including a non-speaking role in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's Mutiny on the Bounty (1935). This helped him gain a contract with Samuel Goldwyn.

Parts, initially small, in major motion pictures followed, including Dodsworth (1936), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), and The Prisoner of Zenda (1937). By 1938, he was starring as a leading man in films such as Wuthering Heights (1939). Upon the outbreak of the Second World War, Niven returned to Britain and rejoined the army, being recommissioned as a lieutenant. In 1942, he co-starred in the morale-building film about the development of the renowned Supermarine Spitfire fighter plane, The First of the Few (1942).

He went on to receive the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in Separate Tables (1958). Other notable films during this time period include A Matter of Life and Death (1946), The Bishop's Wife (1947), Enchantment (1948), The Elusive Pimpernel (1950), The Moon Is Blue (1953), Around the World in 80 Days (1956), My Man Godfrey (1957), The Guns of Navarone (1961), Murder by Death (1976), and Death on the Nile (1978). He also earned acclaim and notoriety playing Sir Charles Lytton in The Pink Panther (1963) and James Bond in Casino Royale (1967).

Early life and family

[edit]James David Graham Niven was born on 1 March 1910 at Belgrave Mansions, Grosvenor Gardens, London, to William Edward Graham Niven (1878–1915) and his wife, Henrietta Julia (née Degacher) Niven (1878–1932).[3] He was named David after his birth on St David's Day. Niven later claimed he was born in Kirriemuir, in the Scottish county of Angus in 1909, but his birth certificate disproves this.[4] He had two older sisters and a brother: Margaret Joyce Niven (1900–1981), Henry Degacher Niven (1902–1953), and the sculptor Grizel Rosemary Graham Niven (1906–2007), who created the bronze sculpture Bessie that is presented to the annual winners of the Women's Prize for Fiction.

Niven's father, William Niven, was of Scottish descent; he was killed in the First World War serving with the Berkshire Yeomanry during the Gallipoli campaign on 21 August 1915. He is buried in Green Hill Cemetery, Turkey, in the Special Memorial Section in Plot F. 10.[5] Niven's paternal great-grandfather and namesake, David Graham Niven, (1811–1884) was from St Martins, a village in Perthshire. A physician, he married in Worcestershire, and lived in Pershore.

Niven's mother, Henriette, was born in Brecon, Wales. Her father was Captain (brevet Major) William Degacher (1841–1879) of the 1st Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot, who was killed at the Battle of Isandlwana during the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879.[6] Although born William Hitchcock, in 1874, he and his older brother Lieutenant Colonel Henry Degacher (1835–1902), both followed their father, Walter Henry Hitchcock, in taking their mother's maiden name of Degacher.[7][8] Henriette's mother was Julia Caroline Smith, the daughter of Lieutenant General James Webber Smith CB.

After her husband's death in Turkey in 1915, Henrietta Niven remarried in London in 1917 to Conservative politician and diplomat Sir Thomas Walter Comyn-Platt (1869–1961).[9] David and his sister Grizel were close, and both loathed Comyn-Platt. The family moved to Rose Cottage in Bembridge on the Isle of Wight after selling their London home.[10] In his 1971 biography, The Moon's a Balloon, Niven wrote fondly of his childhood home:

It became necessary for the house in London to be sold and our permanent address was now as advertised—a cottage which had a reputation for unreliability. When the East wind blew, the front door got stuck and when the West wind blew, the back door could not be opened—only the combined weight of the family seemed to keep it anchored to the ground. I adored it and was happier there than I had ever been, especially because, with a rare flash of genius, my mother decided that during the holidays she would be alone with her children. Uncle Tommy [Comyn-Platt] was barred—I don't know where he went—to the Carlton Club I suppose.[10]

Literary editor and biographer, Graham Lord, wrote in Niv: The Authorised Biography of David Niven, that Comyn-Platt and Niven's mother may have been in an affair well before her husband's death in 1915 and that Comyn-Platt was actually Niven's biological father, a supposition that had some support among Niven's siblings. In a review of Lord's book, Hugh Massingberd from The Spectator stated photographic evidence did show a strong physical resemblance between Niven and Comyn-Platt that "would appear to confirm these theories, though photographs can often be misleading."[11] Niven is said to have revealed that he knew Comyn-Platt was his real father a year before his own death in 1983.[12]

After his mother remarried, Niven's stepfather had him sent away to boarding school. In The Moon's a Balloon, Niven described the bullying, isolation, and abuse he endured as a six-year-old. He said that older pupils would regularly assault younger boys, while the schoolmasters were not much better. Niven wrote of one sadistic teacher:

Mr Croome, when he tired of pulling ears halfway out of our heads (I still have one that sticks out almost at right-angles thanks to this son of a bitch) and delivering, for the smallest mistake in Latin declension, backhanded slaps that knocked one off one's bench, delighted in saying, 'Show me the hand that wrote this' — then bringing down the sharp edge of a heavy ruler across the offending wrist.[13]

Years later, after joining the British Army, a vengeful Niven decided to return to the boarding school to pay a call on Mr Croome but he found the place abandoned and empty.[13]

While attending school – as was customary for the time – Niven received many instances of corporal punishment owing to his inclination for pranks. It was this behaviour that finally led to his expulsion from his next school, Heatherdown Preparatory School, at the age of 10½. This ended his chances for Eton College, a significant blow to his family. After failing to pass the naval entrance exam because of his difficulty with maths, Niven attended Stowe School, a newly created public school led by headmaster J. F. Roxburgh, who was unlike any of Niven's previous headmasters. Thoughtful and kind, he addressed the boys by their first names, allowed them bicycles, and encouraged and nurtured their personal interests. Niven later wrote, "How he did this, I shall never know, but he made every single boy at that school feel that what he said and what he did were of real importance to the headmaster."[13]

In 1928, while she was on holiday in Bembridge, 15-year-old Margaret Whigham (the future socialite and Duchess of Argyll) had a sexual encounter with 18-year-old Niven, resulting in her pregnancy. Furious, her father rushed her to a London nursing home for a secret abortion. "All hell broke loose," remembered Elizabeth Duckworth, the Whigham family cook. Margaret Whigham adored Niven until the day he died; she was among the VIP guests at his London memorial service in 1983.[14]

Military service

[edit]In 1928, Niven attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He graduated in 1930 with a commission as a second lieutenant in the British Army.[15]

He did well at Sandhurst, which gave him the "officer and gentleman" bearing that was his trademark. He requested assignment to the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders or the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment), then jokingly wrote on the form, as his third choice, "anything but the Highland Light Infantry" (because that regiment wore tartan trews rather than the kilt). He was assigned to the HLI, with which he served for two years in Malta and then for a few months in Dover. In Malta, he became friends with the maverick Michael Trubshawe, and served under Roy Urquhart, future commander of the British 1st Airborne Division.[16] On 21 October 1956, in an episode of the game show What's My Line?, Niven, as a member of the celebrity panel, was reacquainted with one of his former enlisted men. Alexander McGeachin was a guest and when his turn in the questioning came up, Niven asked, "Were you in a famous British regiment on Malta?" After McGeachin affirmed that he was, Niven quipped, "Did you have the misfortune to have me as your officer?" At that point, Niven had a brief but pleasant reunion.[17]

Niven grew tired of the peacetime army. Though promoted to lieutenant on 1 January 1933,[18] he saw no opportunity for further advancement. His ultimate decision to resign came after a lengthy lecture on machine guns, which was interfering with his plans for dinner with a particularly attractive young lady. At the end of the lecture, the speaker (a major general) asked if there were any questions. Showing the typical rebelliousness of his early years, Niven asked, "Could you tell me the time, sir? I have to catch a train."[16]

After being placed under close-arrest for this act of insubordination, Niven finished a bottle of whisky with the officer who was guarding him: Rhoddy Rose (later Colonel R. L. C. Rose, DSO, MC).[19] With Rose's assistance, Niven was allowed to escape from a first-floor window. He then headed for the United States. While crossing the Atlantic, Niven resigned his commission by telegram on 6 September 1933.[20] In New York City, Niven began a brief and unsuccessful career in whisky sales, followed by a stint in horse rodeo promotion in Atlantic City, New Jersey. After detours to Bermuda and Cuba, he arrived in Hollywood in 1934.

Film career

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

1935–1938: Early roles

[edit]When Niven presented himself at Central Casting, he learned that he needed a work permit to reside and work in the United States. Since this required leaving the US, he went to Mexico, where he worked as a "gun-man", cleaning and polishing the rifles of visiting American hunters. He received his resident alien visa from the American consulate when his birth certificate arrived from Britain. He returned to the US and was accepted by Central Casting as "Anglo-Saxon Type No. 2,008." Among the initial films in which he can be seen are Barbary Coast (1935) and Mutiny on the Bounty (1935). He secured a small role in A Feather in Her Hat (1935) at Columbia before returning to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for a bit role, billed as David Nivens, in Rose Marie (1936).

Niven's role in Mutiny on the Bounty brought him to the attention of independent film producer Samuel Goldwyn, who signed him to a contract and established his career. For Goldwyn, Niven again had a small role in Splendor (1935). He was lent to MGM for a minor part in Rose Marie (1936), then a larger one in Palm Springs (1936) at Paramount. His first sizeable role for Goldwyn came in Dodsworth (1936), playing a man who flirts with Ruth Chatterton. In that same year he was again loaned out, to 20th Century Fox to play Bertie Wooster in Thank You, Jeeves! (1936), before finally landing a sizeable role as a soldier in The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) at Warners, an Imperial adventure film starring his housemate at the time, Errol Flynn. Niven was fourth billed in Beloved Enemy (1936) for Goldwyn, supporting Merle Oberon with whom he became romantically involved. Universal used him in We Have Our Moments (1937) and he had another good supporting role in David O. Selznick's The Prisoner of Zenda (1937).

1938–1939: Leading man

[edit]

Fox Studios gave him the lead in a B picture, Dinner at the Ritz (1938) and he again had a supporting role in Bluebeard's Eighth Wife (1938) directed by Ernst Lubitsch at Paramount. Niven was one of the four heroes in John Ford's Four Men and a Prayer (1938), also with Fox. He remained with Fox to play the part of a fake love interest in Three Blind Mice (1938). Niven joined what became known as the Hollywood Raj, a group of British actors in Hollywood which included Rex Harrison, Boris Karloff, Stan Laurel, Basil Rathbone, Ronald Colman, Leslie Howard,[21] and C. Aubrey Smith. According to his autobiography, Errol Flynn and he were firm friends and rented Rosalind Russell's house at 601 North Linden Drive as a bachelor pad.

Niven graduated to star parts in "A" films with The Dawn Patrol (1938) remake at Warners; although he was billed below Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone, it was a leading role and the film did excellent business. Niven was reluctant to take a supporting part in Wuthering Heights (1939) for Goldwyn, but eventually relented and the film was a big success. RKO borrowed him to play Ginger Rogers' leading man in the romantic comedy Bachelor Mother (1939), which was another big hit. Goldwyn used him to support Gary Cooper in the adventure tale The Real Glory (1939), and Walter Wanger cast him opposite Loretta Young in Eternally Yours (1939). Finally, Goldwyn granted Niven a lead part, the title role as the eponymous gentleman safe-cracker in Raffles (1939).

1939–1945: Second World War

[edit]The day after Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Niven returned home and rejoined the British Army. He was alone among British stars in Hollywood in doing so; the British Embassy advised most actors to stay.[22]

Niven was recommissioned as a lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) on 25 February 1940,[23] and was assigned to a motor training battalion. He wanted something more exciting, however, and transferred to the Commandos. He was assigned to a training base at Inverailort House in the Western Highlands. Niven later claimed credit for bringing future Major General Sir Robert Laycock to the Commandos. Niven commanded "A" Squadron GHQ Liaison Regiment, better known as "Phantom". He was promoted to war-substantive captain on 18 August 1941.[24]

Niven also worked with the Army Film and Photographic Unit. His work included a small part in the deception operation that used minor actor M. E. Clifton James to impersonate General Sir Bernard Montgomery. During his work with the AFPU, Peter Ustinov, one of the script-writers, had to pose as Niven's batman. Niven explained in his autobiography that there was no military way that he, a lieutenant-colonel, and Ustinov, who was only a private, could associate, other than as an officer and his subordinate, hence their strange "act". In 1978, Niven and Ustinov would star together in a film adaptation of Agatha Christie's Death on the Nile.

He acted in two wartime films not formally associated with the AFPU, but both made with a firm view to winning support for the British war effort, especially in the United States. These were The First of the Few (1942), directed by Leslie Howard, and The Way Ahead (1944), directed by Carol Reed. Ustinov also played a large supporting role as a Frenchman in The Way Ahead.

Niven was also given a significant if largely unheralded role in the creation of SHAEF's military radio efforts conceived to provide entertainment to American, British and Canadian forces in England and Europe. In 1944 he worked extensively with the BBC and SHAEF to expand these broadcast efforts. He also worked extensively with Major Glenn Miller, whose Army Air Force big band, formed in the US, was performing and broadcasting for troops in England. Niven played a role in the operation to move the Miller band to France prior to Miller's December 1944 disappearance while flying over the English Channel.

On 14 March 1944, Niven was promoted war-substantive major (temporary lieutenant-colonel).[25] He took part in the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944, although he was sent to France several days after D-Day. He served in "Phantom", a secret reconnaissance and signals unit which located and reported enemy positions,[26] and kept rear commanders informed on changing battle lines. Niven was posted at one time to Chilham in Kent.

Niven had particular scorn for those newspaper columnists covering the war who typed out self-glorifying and excessively florid prose about their meagre wartime experiences. Niven stated, "Anyone who says a bullet sings past, hums past, flies, pings, or whines past, has never heard one – they go crack!" He gave a few details of his war experience in his autobiography, The Moon's a Balloon: his private conversations with Winston Churchill, the bombing of London, and what it was like entering Germany with the occupation forces. Niven first met Churchill at a dinner party in February 1940. Churchill singled him out from the crowd and stated, "Young man, you did a fine thing to give up your film career to fight for your country. Mark you, had you not done so – it would have been despicable."[16]

A few stories have surfaced. About to lead his men into action, Niven eased their nervousness by telling them, "Look, you chaps only have to do this once. But I'll have to do it all over again in Hollywood with Errol Flynn!" Asked by suspicious American sentries during the Battle of the Bulge who had won the World Series in 1943, he answered, "Haven't the foggiest idea, but I did co-star with Ginger Rogers in Bachelor Mother!"[27]

Niven ended the war as a lieutenant-colonel. On his return to Hollywood after the war, he received the Legion of Merit, an American military decoration.[28] It honoured Niven's work in setting up the BBC Allied Expeditionary Forces Programme, a radio news and entertainment station for the Allied forces.[29][30]

1946–1950: Postwar career

[edit]Niven resumed his career while still in England, playing the lead in A Matter of Life and Death (1946), from the team of Powell and Pressburger. The film was critically acclaimed, popular in England and was selected as the first Royal Film Performance. Niven returned to Hollywood and encountered tragedy when his first wife died after falling down a flight of stairs at a party. Goldwyn lent him to play Aaron Burr in Magnificent Doll (1946) opposite Ginger Rogers, then to Paramount for The Perfect Marriage (1947) with Loretta Young and Enterprise Productions for The Other Love (1947). For Goldwyn he supported Cary Grant and Young in The Bishop's Wife (1947).

Niven returned to England when Goldwyn lent him to Alexander Korda to play the title role in Bonnie Prince Charlie (1948), a notorious box office flop. Back in Hollywood Niven was in Goldwyn's Enchantment (1948) with Teresa Wright. At Warner Bros he was in a comedy A Kiss in the Dark (1948) with Jane Wyman, then he appeared opposite Shirley Temple in the comedy A Kiss for Corliss (1949). None of these films was successful at the box office and Niven's career was struggling.

He returned to Britain to play the title role in The Elusive Pimpernel (1950) from Powell and Pressberger, which was to have been financed by Korda and Goldwyn. Goldwyn pulled out and the film did not appear in the US for three years. Niven had a long, complex relationship with Goldwyn, who gave him his first start, but the dispute over The Elusive Pimpernel and Niven's demands for more money led to a long estrangement between the two in the 1950s.[31]

1951–1964: Renewed acclaim

[edit]

Niven struggled for a while to recapture his former position. He supported Mario Lanza in a musical at MGM, The Toast of New Orleans (1950). He then went to England and appeared in a musical with Vera-Ellen, Happy Go Lovely (1951); it was little seen in the US but was a big hit in Britain. He had a support role in MGM's Soldiers Three (1951) similar to those early in his career. Niven had a far better part in the British war film Appointment with Venus (1952), which was popular in England. The Lady Says No (1952) was a poorly received American comedy at the time. Niven decided to try Broadway, appearing opposite Gloria Swanson in Nina (1951–52). The play ran for only 45 performances but it was seen by Otto Preminger, who decided to cast Niven in the film version of the play The Moon Is Blue (1953). As preparation Preminger, who had directed the play in New York, insisted that Niven appear on stage in the West Coast run. The Moon Is Blue, a sex comedy, became notorious when it was released without a Production Code Seal of Approval; it was a big hit and Niven won a Golden Globe Award for his role.[citation needed]

Niven's next few films were made in England: The Love Lottery (1954), a comedy; Carrington V.C. (1954), a drama that earned Niven a BAFTA nomination for Best Actor; Happy Ever After (1954), a comedy with Yvonne de Carlo, which was hugely popular in Britain. In Hollywood, he had a thankless role as the villain in an MGM swashbuckler, The King's Thief (1955). He had a better part in The Birds and the Bees (1956), portraying a conman in a remake of The Lady Eve (1941), in which Niven played a third-billed supporting role under American television comedian George Gobel and leading lady Mitzi Gaynor. Niven also appeared in the British romantic comedy The Silken Affair (1956) with Geneviève Page the same year.

Niven's professional fortunes were restored when cast as Phileas Fogg in Around the World in 80 Days (1956), a huge hit at the box office. It also won the Academy Award for Best Picture. He followed it with Oh, Men! Oh, Women! (1957); The Little Hut (1957), from the writer of The Moon is Blue and a success at the box office; My Man Godfrey (1957), a screwball comedy; and Bonjour Tristesse (1958), for Preminger. Niven worked in television. He appeared several times on various short-drama shows and was one of the "four stars" of the dramatic anthology series Four Star Playhouse, appearing in 33 episodes. The show was produced by Four Star Television, which was co-owned and founded by Niven, Ida Lupino, Dick Powell and Charles Boyer. The show ended in 1955, but Four Star Television became a highly successful TV production company.[citation needed]

Niven is the only person to win an Academy Award at the ceremony he was hosting.[32] He won the 1958 Academy Award for Best Actor for his role as Major David Angus Pollock in Separate Tables, his only nomination for an Oscar. Appearing on-screen for only 23 minutes in the film, this is the briefest performance ever to win a Best Actor Oscar.[citation needed] He was also a co-host of the 30th, 31st, and 46th Academy Awards ceremonies. After Niven had won the Academy Award, Goldwyn called with an invitation to his home. In Goldwyn's drawing-room, Niven noticed a picture of himself in uniform which he had sent to Goldwyn from Britain during the Second World War. In happier times with Goldwyn, he had observed this same picture sitting on Goldwyn's piano. Now years later, the picture was still in exactly the same spot. As he was looking at the picture, Goldwyn's wife Frances said, "Sam never took it down."[16]

With an Academy Award to his credit, Niven's career continued to thrive. In 1959, he became the host of his own TV drama series, The David Niven Show, which ran for 13 episodes that summer. He played the lead in some comedies: Ask Any Girl (1959), with Shirley MacLaine; Happy Anniversary (1959) with Mitzi Gaynor; and Please Don't Eat the Daisies (1960) with Doris Day, a big hit.

Even more popular was the action film The Guns of Navarone (1961) with Gregory Peck and Anthony Quinn. This role led to him being cast in further war and/or action films: The Captive City (1962); The Best of Enemies (1962); Guns of Darkness (1962); 55 Days at Peking (1963) with Charlton Heston and Ava Gardner. Niven returned to comedy with The Pink Panther (1963) also starring Peter Sellers, another huge success at the box office. Less so was the comedy Bedtime Story (1964) with Marlon Brando. In 1964, Charles Boyer, Gig Young and top-billed Niven appeared in the Four Star series The Rogues. Niven played Alexander 'Alec' Fleming, one of a family of retired con-artists who now fleece villains in the interests of justice. This was his only recurring role on television, and the series was originally set up to more or less revolve between the three leads in various combinations (one-lead, two-lead and three-lead episodes), although the least otherwise busy Gig Young wound up carrying most of the series. The Rogues ran for only one season, but won a Golden Globe award.[citation needed]

1965–1982: Later films

[edit]In 1965, Niven made two films for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer: the Peter Ustinov-directed Lady L, supporting Paul Newman and Sophia Loren, and Where the Spies Are, as a doctor-turned-secret agent – MGM hoped it would lead to a series, but this did not happen. After the horror film Eye of the Devil (1966), Niven appeared as James Bond in Casino Royale (1967), and is, with the exception of Sean Connery in Never Say Never Again, the only other man to ever portray Bond in a non-Eon Productions film. Niven had been Bond creator Ian Fleming's first choice to play Bond in Dr. No. Casino Royale co-producer Charles K. Feldman said later that Fleming had written the book with Niven in mind, and therefore had sent a copy to Niven.[33] Niven was the only actor who played James Bond mentioned by name in the text of a Fleming novel. In chapter 14 of You Only Live Twice, pearl diver Kissy Suzuki refers to Niven as "the only man she liked in Hollywood", and the only person who "treated her honourably" there.

Niven made some popular comedies, Prudence and the Pill (1968) and The Impossible Years (1968). Less widely seen was The Extraordinary Seaman (1969). The Brain (1969), a French comedy with Bourvil and Jean-Paul Belmondo, was the most popular film at the French box office in 1969 but was not widely seen in English-speaking countries. He did a war drama Before Winter Comes (1969) then returned to comedy in The Statue (1971). Niven was in demand throughout the last decade of his life: King, Queen, Knave (1972); Vampira (1974); Paper Tiger (1975); No Deposit, No Return (1976), a Disney comedy; Murder By Death (1976), Candleshoe (1977), one of several stars in a popular comedy; Death on the Nile (1978), one of many stars and another hit; A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square (1979); Escape to Athena (1979), produced by his son; Rough Cut (1980), supporting Burt Reynolds; and The Sea Wolves (1980), a wartime adventure film.

In 1974, while Niven was co-hosting the 46th Annual Oscars ceremony, a naked man (Robert Opel) appeared behind him, "streaking" across the stage. In what instantly became a live-TV classic moment, Niven responded "Isn't it fascinating to think that probably the only laugh that man will ever get in his life is by stripping off and showing his shortcomings?"[34] That same year, he hosted David Niven's World for London Weekend Television, which profiled contemporary adventurers such as hang gliders, motorcyclists, and mountain climbers: it ran for 21 episodes. In 1975, he narrated The Remarkable Rocket, a short animation based on a story by Oscar Wilde. Niven's last sizeable film part was in Better Late Than Never (1983). In July 1982, Blake Edwards brought Niven back for cameo appearances in two final "Pink Panther" films (Trail of the Pink Panther and Curse of the Pink Panther), reprising his role as Sir Charles Lytton. By this time, Niven was having serious health problems. When the raw footage was reviewed, his voice was inaudible, and his lines had to be dubbed by Rich Little. Niven only learned of it from a newspaper report. This was his last film appearance.[citation needed]

Writing

[edit]

Niven wrote four books. The first, Round the Rugged Rocks (published simultaneously in the US under the title Once Over Lightly), was a novel that appeared in 1951 and was forgotten almost at once. The plot was plainly autobiographical (although not recognised as such at the time of publication), involving a young soldier, John Hamilton, who leaves the British Army, becomes a liquor salesman in New York, is involved in indoor horse racing, goes to Hollywood, becomes a deckhand on a fishing boat, and finally ends up as a highly successful film star.

In 1971, he published his autobiography, The Moon's a Balloon, which was well received, selling over five million copies. He followed this with Bring On the Empty Horses in 1975, a collection of entertaining reminiscences from the Golden Age of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. As more of a raconteur rather than an accurate memoirist, it seems that Niven recounted many incidents from a first-person perspective that actually happened to other people, among them Cary Grant.[4] This liberal borrowing and embroidering of his personal history was also said to be the reason why he persistently refused to appear on This Is Your Life.[35] Niven's penchant for exaggeration and embroidery is particularly apparent when comparing his written descriptions of his early film appearances (especially Barbary Coast and A Feather in her Hat), and his Oscar acceptance speech, with the actual filmed evidence. In all three examples, the reality is significantly different from Niven's heavily fictionalised accounts as presented in The Moon's a Balloon and related in various chat show appearances.

In 1981 Niven published a second and much more successful novel, Go Slowly, Come Back Quickly, which was set during and after the Second World War, and which drew on his experiences during the war and in Hollywood. He was working on a third novel at the time of his death.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]

While on leave in 1940, Niven met Primula "Primmie" Susan Rollo (18 February 1918 – 21 May 1946), the daughter of London lawyer William H.C. Rollo. After a whirlwind romance, they married on 16 September 1940. A son, David Jr., was born in December 1942 and a second son, James Graham Niven, on 6 November 1945. Primmie died at the age of 28, only six weeks after the family moved to the US. She fractured her skull in a fall in the Beverly Hills, California home of Tyrone Power, while playing a game of sardines. She had walked through a door believing it to be a closet, but instead, it led to a stone staircase to the basement.[36][37]

In 1948, Niven met and married Hjördis Paulina Tersmeden (née Genberg, 1919–1997), a divorced Swedish fashion model. He recounted their meeting:

I had never seen anything so beautiful in my life – tall, slim, auburn hair, up-tilted nose, lovely mouth and the most enormous grey eyes I had ever seen. It really happened the way it does when written by the worst lady novelists ... I goggled. I had difficulty swallowing and had champagne in my knees.[16]

According to friends, the relationship between Niven and Hjördis was turbulent.[38][39]

In 1960, Niven bought a chalet in Château-d'Œx near Gstaad in Switzerland for financial reasons, living near expatriate friends including Deborah Kerr, Peter Ustinov, and Noël Coward.[40][41] It is believed by some that Niven's choice to become a tax exile may have been one reason why he never received a British honour.[42] However, Kerr, Ustinov, and Coward were all honoured. A 2009 biography of Niven contained assertions that he had an affair with Princess Margaret, who was 20 years his junior.[43] He also became close friends with William F. Buckley Jr. and his wife Pat; Buckley wrote a memorial tribute to him in Miles Gone By (2004).

Niven divided his time in the 1960s and 1970s between his chalet in Château-d'Œx[44] and Cap Ferrat on the Côte d'Azur in the south of France.[40]

Death and legacy

[edit]In 1980 Niven began experiencing fatigue, muscle weakness and a warble in his voice. His 1981 interviews on the talk shows of Michael Parkinson and Merv Griffin alarmed family and friends; viewers wondered if Niven had either been drinking or suffered a stroke. He blamed his slightly slurred voice on the shooting schedule of the film he had been making, Better Late Than Never. He was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, also known as motor neurone disease) later that year. His final appearance in Hollywood was hosting the 1981 American Film Institute tribute to Fred Astaire.

In February 1983, using a false name to avoid publicity, Niven was hospitalised for 10 days, ostensibly for a digestive problem. Afterwards, he returned to his chalet at Château-d'Œx. Though his condition continued to worsen he refused to return to the hospital, a decision supported by his family. He died at his chalet on 29 July 1983, aged 73.[45][46][47] Niven was buried on 2 August in the local cemetery of Château-d'Œx.[48]

A Thanksgiving service for Niven was held at St Martin-in-the-Fields, London, on 27 October 1983. The congregation of 1,200 included Prince Michael of Kent, Margaret Campbell, Duchess of Argyll, Sir John Mills, Sir Richard Attenborough, Trevor Howard, David Frost, Joanna Lumley, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Laurence Olivier.[49] Biographer Graham Lord wrote, "the biggest wreath, worthy of a Mafia Godfather's funeral, was delivered from the porters at London's Heathrow Airport, along with a card that read: 'To the finest gentleman who ever walked through these halls. He made a porter feel like a king.'"[50]

In 1985, Niven was included in a series of British postage stamps, along with Sir Alfred Hitchcock, Sir Charles Chaplin, Peter Sellers and Vivien Leigh, to commemorate "British Film Year".[51] Niven's appearance was used as inspiration for that of Commander Norman in the Thunderbirds franchise, as well as DC Comics villain Sinestro.[52]

Niven's Bonjour Tristesse co-star, Mylène Demongeot, declared about him, in a 2015 filmed interview:

"He was like a Lord, he was part of those great actors who were extraordinary like Dirk Bogarde, individuals with lots of class, elegance and humour. I only saw David get angry once. Preminger had discharged him for the day but eventually asked to get him. I said, sir, you had discharged him, he left for Deauville to gamble at the casino. So we rented a helicopter so they immediately went and grabbed him. Two hours later, he was back, full of rage. There I saw David lose his British phlegm, his politeness and class. It was royal. [Laughs]."[53]

Acting credits

[edit]Accolades

[edit]| Year | Association | Category | Nominated work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Academy Award | Best Actor | Separate Tables | Won | |

| 1954 | BAFTA Award | Best British Actor | Court Martial | Nominated | |

| 1955 | Emmy Awards | Best Actor in a Single Performance | Four Star Playhouse | Nominated | |

| 1957 | Nominated | ||||

| 1953 | Golden Globe Awards | Best Actor in a Musical or Comedy – Motion Picture | The Moon is Blue | Won | |

| 1957 | My Man Godfrey | Nominated | |||

| 1958 | Best Actor in a Drama – Motion Picture | Separate Tables | Won |

Bibliography

[edit]- Niven, David (1951). Round the Rugged Rocks. London: The Cresset Press.

- Niven, David (1971). The Moon's a Balloon. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-340-15817-4.

- Niven, David (1975). Bring on the Empty Horses. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-89273-2.

- Niven, David (1981). Go Slowly, Come Back Quickly. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-10690-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Lord, Graham (14 December 2004). NIV: The Authorized Biography of David Niven. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-32863-4.

- Morley, Sheridan (5 September 2016). The Other Side of the Moon: The Life of David Niven. Dean Street Press. ISBN 978-1-911413-63-9.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Niven, (James) David Graham (1910–1983), actor and author". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31503. Retrieved 8 April 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Obituaries". The Times. 30 July 1983.

- ^ Morley, Sheridan (1997). David Niven, Brief Lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 413. ISBN 0198600879.

- ^ a b Morley, Sheridan (1985). The Other Side of the Moon. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-340-39643-1.

- ^ "Casualty details—Niven, William Edward Graham". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ^ "Marriages". The Times. 26 October 1888.

- ^ "Notices". The Times. 18 February 1874. p. 1.

- ^ "Henry James Degacher CB". www.britishempire.co.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "1917 – David Niven's mother marries Thomas Comyn Platt". hjordisniven.com. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ a b "David Niven's idyllic childhood home comes up for sale: 'I adored it and was happier there than I had ever been'". Country Life. 23 January 2020.

Part of the reason that the young Niven enjoyed his school holidays in Bembridge so much is that his mother saw very clearly that her two teenage sons needed space and freedom to let their hair down — so much so, in fact, that she built an extension to the rear of the house which was quickly dubbed the 'Sin Wing'. [When] David and his brother used to come in rather noisily at night [...] his mother got a bit cross so she built two bedrooms and a bathroom at the back.

- ^ Massingberd, Hugh (15 November 2003). "It's being so cheerful that keeps me going". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ "The flawed real life of the perfect movie gentleman". Irish Independent. 19 July 2009.

- ^ a b c Niven, David (1971). The Moon's a Balloon (Reprint (2005)). Penguin Books Limited. pp. 38–45. ISBN 9780140239249.

- ^ Lord, Graham (2004). Niv: The Authorised Biography of David Niven. Orion. p. 420.

- ^ "No. 33575". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 January 1930. pp. 651–652.

- ^ a b c d e David Niven (1971). The Moon's a Balloon. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-340-15817-4.

- ^ What's My Line? – Lerner & Loewe; Bishop Sheen; David Niven [panel] (21 October 1956) on YouTube

- ^ "No. 33907". The London Gazette. 31 January 1933. p. 674.

- ^ "Lieutenant-Colonel David Rose". The Daily Telegraph. 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "No. 33975". The London Gazette. 5 September 1933. p. 5801.

- ^ Eforgan, E. (2010) Leslie Howard: The Lost Actor. London: Vallentine Mitchell; p. 94 ISBN 978-0-85303-971-6

- ^ Friedrich, Otto (1986). City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-520-20949-4.

- ^ "No. 34823". The London Gazette (Supplement). 5 September 1933. p. 1978.

- ^ The Quarterly Army List (October–December 1943: Part II). London: HM Stationery Office. 1943. p. 1368b.

- ^ The Quarterly Army List (April–June 1945: Part II). London: HM Stationery Office. 1945. p. 1368b.

- ^ "Five Film Stars' Wartime Roles". Imperial War Museums.

- ^ "David Niven was the only British star in Hollywood to enlist during WWII". 18 August 2016.

- ^ "No. 37340". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 November 1945. p. 5461.

- ^ "Recommendation for Award for Niven, John David Rank: Lieutenant Colonel" (fee usually required to view full pdf of original recommendation). DocumentsOnline. The National Archives. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ "No. 37340". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 November 1945. p. 5461.

- ^ "David Niven's Own Story". The Australian Women's Weekly. National Library of Australia. 15 September 1971. p. 15. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Keegan, Rebecca (20 February 2019). "The Politics of Oscar: Inside the Academy's Long, Hard Road to a Hostless Show". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ "Ian Fleming, Author or Spy?". www.hmss.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- ^ "Oscar streaker". YouTube. 19 February 2008. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ "Why David Niven and the amateurs behind Jamaica Inn will always be on Separate Tables". Borehamwood Times. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Karin J. Fowler (1995) David Niven: a Bio-Biography, Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313280443

- ^ Sunday Times (Perth, WA: 1902–1954) "David Niven's wife in death crash" 26 May 1946, P.3 Retrieved 12 January 2016

- ^ "The flawed real life of the perfect movie gentleman". Irish Independent. Dublin. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Bradley, Charley (27 February 2022). "David Niven wife: Roger Moore claimed Niven's partner 'was a b**** to him'". Daily Express. London. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b Michael Munn (20 March 2014). David Niven: The Man Behind the Balloon. Aurum Press. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-1-78131-372-5.

- ^ Fowler, Karin J. (1 January 1995). David Niven: A Bio-bibliography. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-0-313-28044-3.

- ^ Greenfield, George (1 January 1995). A Smattering of Monsters: A Kind of Memoir. Camden House Publishing. pp. 187–. ISBN 978-1-57113-071-6.

- ^ Munn, Michael (24 May 2009). "Oh God, I wanted her to die". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ "Ch. David Niven 7: Château-d'Oex". map.search.ch. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Donnelley, Paul (2003). Fade to Black: A Book of Movie Obituaries. Music Sales Group. p. 522. ISBN 0-711-99512-5.

- ^ Pace, Eric (30 July 1983). "David Niven Dead at 73; Witty Actor Won Oscar". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Pace, Eric (30 July 1983). "David Niven Dead at 73; Witty Actor Won Oscar". The New York Times. p. 2.

- ^ Brooks, Patricia; Brooks, Jonathan (2006). Laid to Rest in California: A Guide to the Cemeteries and Grave Sites of the Rich and Famous. Globe Pequot. p. 522. ISBN 0-762-74101-5.

- ^ Niv by Graham Lord, Orion, 2004, p. 420

- ^ "In Thespian Praise of: David Niven". Paulburgin.blogspot.com. 25 January 2006. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ Walker, Alexander. Vivien: The Life of Vivien Leigh, pp. 303, 304. Grove Press, 1987.

- ^ Brown, Jeremy (10 June 2007). "WIZARD INSIDER: SINESTRO". Wizard. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ Mac Mahon Filmed Conferences Paris (5 July 2015). "Rencontre avec mylène demongeot". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

External links

[edit]- David Niven at the BFI's Screenonline

- David Niven at the British Film Institute[better source needed]

- "Archival material relating to David Niven". UK National Archives.

- David Niven at the Internet Broadway Database

- David Niven at IMDb

- David Niven at the TCM Movie Database

- David Niven at Find a Grave

- Legionnaires of the Legion of Merit

- 1910 births

- 1983 deaths

- 20th-century English male actors

- 20th-century English memoirists

- 20th-century English novelists

- Writers from the City of Westminster

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- British Army Commandos officers

- British Army personnel of World War II

- British expatriates in Switzerland

- British expatriate male actors in the United States

- Deaths from motor neuron disease

- English male film actors

- English male stage actors

- English male television actors

- English people of French descent

- English people of Scottish descent

- English people of Welsh descent

- Foreign recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

- Highland Light Infantry officers

- Male actors from London

- Neurological disease deaths in Switzerland

- People educated at Heatherdown School

- People educated at Stowe School

- People from Buckland, Oxfordshire

- People from Château-d'Œx

- Military personnel from the City of Westminster

- Rifle Brigade officers

- English autobiographers

- Actors from the City of Westminster

- People from Victoria, London

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players

- Niven family