Horn & Hardart

First Automat, 818–820 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia (1904 postcard) | |

| Company type | Privately held company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Restaurants |

| Founded | 1888 (partnership) 1902 (first automat) |

Key people | Joseph Horn, Frank Hardart |

| Revenue | USD |

Horn & Hardart was a food services company in the United States noted for operating the first food service automats in Philadelphia, New York City, and Baltimore.[1]

Philadelphia's Joseph Horn (1861–1941) and German-born, New Orleans-raised Frank Hardart (1850–1918) opened their first restaurant in Philadelphia, on December 22, 1888. The 11-by-17-foot (3.4 m × 5.2 m) lunchroom at 39 South Thirteenth Street had no tables, only a counter with 15 stools. The location was formerly the print shop of Dunlap & Claypoole, printers to the American Congress and George Washington.[2]

By introducing Philadelphia to New Orleans-style coffee, which Hardart promoted as their "gilt-edge" brew, they made their tiny luncheonette a local attraction. News of the coffee spread, and the business flourished. They incorporated as the Horn & Hardart Baking Company in 1898.

At its peak the company operated in excess of 100 restaurants, as well as a popular chain of retail outlets. The lack of a succession plan, changing demographics, the rapid rise of fast food chains, and poor strategic decisions from the early 1960s on were too much to overcome and the last restaurant was closed in 1991.

History

[edit]

Joseph Horn had traveled in Europe and experienced the revolutionary new form of restaurant known as the Automat, pioneered by Max Sielaff in Berlin. Inspired by the success and decor of this new form of food service that eliminated wait staffs but still served high quality fresh food, Horn persuaded his partner Frank Hardart to open the first automat[3] in the U.S., which made its debut on June 9, 1902,[4] at 818 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia.[5] It was the first non-European restaurant to receive patented vending machines from Sielaff's Automat GmbH factory in Berlin, the creators also of the first chocolate bar vending machine for Ludwig Stollwerck.[4]

Ten years later the first New York Automat opened in Times Square, on July 2, 1912, and later that week, the third opened at Broadway and E 14th St, near Union Square.

In 1924, Horn & Hardart opened retail stores to sell prepackaged automat favorites. Using the advertising slogan, "Less Work for Mother," the company popularized the notion of easily served "take-out" food as an equivalent to "home-cooked" meals.[6]

The Horn & Hardart Automats were particularly popular during the Depression era, when their macaroni and cheese, baked beans, and creamed spinach were staple offerings.[citation needed] In the 1930s, union conflicts resulted in vandalism, as noted by Christopher Gray in The New York Times:

In 1932 the police blamed members of the glaziers union for vandalism against 24 Horn & Hardart and Bickford's restaurants in Manhattan, including the one at 488 Eighth Avenue. Witnesses said that a passenger in a car driving by used a slingshot to damage and even break the plate glass show windows. Glaziers union representatives had complained about nonunion employees installing glass at the restaurants.[7]

By the time of Horn's death in 1941, the business had 157 retail shops and restaurants in the Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore, areas, serving some 500,000 patrons a day.[8] During the 1940s and the 1950s, more than 50 New York Horn & Hardart restaurants served 350,000 customers a day.[citation needed]

In 1953, the company split into two independent public corporations: the New York entity was named the Horn & Hardart Company, the Philadelphia the Horn & Hardart Baking Company. Shares of the first were traded on the American Stock Exchange, and the second the Philadelphia Stock Exchange.[citation needed]

The self-service restaurants operated for nearly a century, with the business' last storefront closing in New York City in 1991.

Operation

[edit]

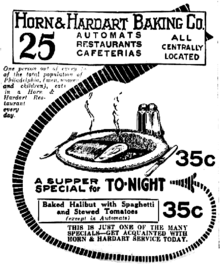

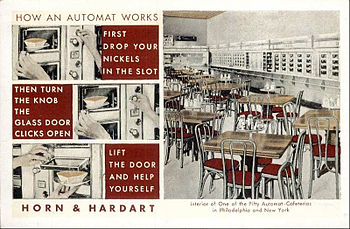

In their heyday, Horn & Hardart automats were popular, busy eateries. They featured prepared foods displayed behind small coin- and token-operated glass-doored windows, beginning with buns, beans, fish cakes, and coffee.[citation needed] As late as the 1950s one could enjoy a large, if somewhat plain, meal for under $1.00. Each stack of dispensers had a metal drum that could be rotated by staff on the other side of the vending wall to refill its windows. Every dispenser had a slot for coins or tokens purchased from a cashier worth up to 75¢ for more expensive items. A knob was rotated to capture the fee and unlock the door. Dispensers were room temperature, heated, or cooled as appropriate.

With success the chain began lunch and dinner entrees, such as fish, beef stew, and Salisbury steak with mashed potatoes.

Carolyn Hughes Crowley described the appeal of the Automats:

In huge rectangular halls filled with shiny, lacquered tables, women with rubber tips on their fingers — "nickel throwers," as they became known — in glass booths gave customers the five-cent pieces required to operate the dispensers. After depositing the appropriate amount the compartment opened to present the desired food to the customer through a small glass. Diners picked up hot foods at buffet-style steam tables. The word "automat" comes from the Greek automatos, meaning "self-acting." Still, the Automats were heavily staffed. As a customer removed a compartment's contents, a worker quickly slipped another sandwich, salad, side dish, or dessert into the vacated chamber.[9]

Promotions

[edit]The Horn and Hardart Children's Hour

[edit]Radio program

[edit]Beginning in 1927, Horn & Hardart sponsored a radio program, The Horn and Hardart Children's Hour, a variety show with a cast of children, including some who as adults became well-known performers (such as Bernadette Peters and Frankie Avalon). The program was broadcast first on WCAU Radio in Philadelphia, hosted by Stan Lee Broza. It was broadcast on NBC Radio in New York during the 1940s and 1950s. The original New York host was Paul Douglas, succeeded by Ralph Edwards and finally Ed Herlihy.[citation needed]

Television program

[edit]The television premiere of The Horn & Hardart Children's Hour appeared on WCAU-TV in Philadelphia in 1948, succeeded by WNBT in New York in 1949, telecast on Sunday mornings. Stan Lee Broza hosted in Philadelphia, and Ed Herlihy in New York.[citation needed]

Decline

[edit]For a long period of time the price of coffee was 5 cents, or one nickel. On November 29, 1950 the price raised to 10 cents, using two nickels.[10]

The restaurant chain remained popular into the 1960s, operating sit-down waitress service restaurants, cafeterias, retail stores, and bakery shops[clarification needed] in addition to its automats. In the late 1960s, efforts were made to update decor, and redecorate some restaurants relevant to surrounding neighborhoods; thus, the Automat on 14th Street was decorated with psychedelic posters. The chain rapidly lost ground to the explosive rise of fast-food chains, which offered cheap fare, a limited menu, and easy to carry take-out.

By the mid-1970s the company began to replace some of its restaurants with its own Burger King franchises.[11] Horn & Hardart further expanded its fast food operations in 1981, acquiring the Bojangles' Famous Chicken n' Biscuits restaurants, which it sold to a California investment company in 1990 for $20 million.[12] More similar restaurant franchises and associations were to follow.

In 1979, Horn & Hardart agreed to buy the Royal Inn in Las Vegas for $7.4 million.[13] By late 1980, the sale had been completed, and the property was rebranded as the Royal Americana Hotel, with a New York theme.[14] A $3.5 million renovation[15] increased the room count to 300.[16] By 1982 though, the hotel was experiencing substantial losses, and Horn & Hardart decided to close it.[15] They reportedly agreed that December to sell the property to an investment group for $15.4 million.[17]

The last New York Horn & Hardart Automat (on the southeast corner of 42nd Street and Third Avenue) closed on April 9, 1991.[18][19] Horn & Hardart continued to own a catalog division; it renamed itself Hanover Direct in 1993. That year the company bought Gump's; it sold it to an investment group in 2005. Hanover Direct purchased International Male in 1987 when founder Gene Burkard retired.[citation needed]

Revivals

[edit]In 1987, Horn & Hardart opened two 1950s themed Dine-O-Mat restaurants in New York. They closed less than two years later.[20]

In 1986 its only remaining Philadelphia area restaurant was in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania.[21] In summer 1987 the company opened another restaurant in Bensalem, Pennsylvania, a second in the Philadelphia area.[22] Its planned square footage was 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2). The space was a former Duff's Cafeteria.[23] In December 1988 it was to open another location in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania.[24]

In the early 1990s, two entrepreneurs bought the Philadelphia company (Horn & Hardart Baking Co.) out of bankruptcy. While they did not open any restaurants, they reproduced a dozen of the most famous food items, including macaroni and cheese, Harvard beets, tapioca pudding, and cucumber salad.[25] The food was packed fresh, refrigerated, and sold in supermarkets throughout Philadelphia and New Jersey. The food was still available up until 2002.[citation needed]

The Horn & Hardart name was used for a now-dormant chain of coffee shops in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The Horn & Hardart Coffee Co. closed its last coffee shop in 2005.[citation needed]

As of 2016, the Horn & Hardart – Bakery Cafe is the name of a coffee shop in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[26]

The assets of the company were purchased in 2015 as Horn & Hardart Coffee. They recreated the original East Coast City Roast and branded coffee was offered as of 2016 on their website. They also offered a subscription service called The Automat Club.[27]

As of November 2022, the official Horn & Hardart website announced that the brand had returned with a recreation of the original Automat Blend of coffee. The website also says the company is in the process of modernizing the Automat and restoring the brand online and in retail. [28] The new CEO, David Arena, published his vision for the company online which he says includes reopening an Automat in the future. [29]

Gallery

[edit]-

Automat in Times Square, circa 1939

-

A brass H&H token

-

1930s-era Automat at 104 West 57th Street near Sixth Avenue showing areas for beverages and pies at right of dining area

In popular culture

[edit]Literature

[edit]- In Paul Auster's 2017 novel 4 3 2 1, Ferguson visits the restaurant, which is described as a place of "twentieth-century American efficiency in its craziest, most delightful incarnation".[30]

- In the 1967 novel, The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E. L. Konigsburg, the main characters eat using coins from the fountain of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Museum exhibits

[edit]- On June 22, 2012, the New York Public Library opened an exhibition on June 22, 2012, titled "Lunch Hour NYC". The exhibition "looks back at more than a century of New York lunches, when the city's early power brokers invented the 'power lunch' ..... and visitors with guidebooks thronged Times Square to eat lunch at the Automat." Among many educational and entertaining items is a fully restored wall of Automat windows. The exhibit was scheduled to run until February 17, 2013.[31]

- The Smithsonian's National Museum of American History previously had displayed in its cafe an ornate 35-foot Automat section, complete with mirrors, marble and marquetry, from Philadelphia's 1902 Horn & Hardart[32] although this exhibit has since been removed. In 2006 Paul and Tom Hardart donated the business records for the Horn and Hardart chain of restaurants and retail stores to the Smithsonian Archives; the records include annual reports, business correspondence, operating manuals, photographs, sales materials, and printed materials such as employee newsletters and clippings.[33]

Music

[edit]- Concerto for Horn and Hardart is a classical music parody written by Peter Schickele, one of many which he attributes to the fictional composer P.D.Q. Bach.[34]

- The song Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend by Leo Robin and Jule Styne mentions the Automat in its lyrics.

Stage productions

[edit]- In the song "Colored Spade" from the musical Hair (1967), the character Hud (a militant African-American) satirically assigns to himself various racial stereotypes including "Table cleaner at Horn & Hardart".[35][36]

- The original Broadway set for the musical The Producers (2001) incorporated some of the Automat.[37]

Television

[edit]- Jack Benny held a promotional, black-tie party to launch his television show The Jack Benny Program on October 29, 1950, at the New York City Automat.[38] Playing on his reputation as a cheapskate, Benny greeted his guests at the door and handed each one a roll of nickels so they could get what they wanted to eat.

- In The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Season 5, Episode 9 "Four Minutes", the H&H Automat is the backdrop for a scene between Midge and Susie in the early part of the episode.

- In Arrested Development, Season 4 Remix: Fateful Consequences, Episode 6 "The Parent Traps", the name Horn & Hardart is referenced as an inneundo between Lucille Austero and Buster Bluth.

Film

[edit]- Metropolitan (1990), the first film of Whit Stillman's classic trilogy, contains a scene in which Tom Townsend and Charie Black have a conversation inside (and then depart the entrance to) the last New York Horn & Hardart Automat at the SE corner of 42nd Street and 3rd Avenue.

- That Touch of Mink (1962), comedy with Cary Grant, Doris Day, and Gig Young who visit the Automat in New York City

- The Automat (2021), documentary by Lisa Hurwitz about the chain featuring Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Colin Powell, Ruth Bader Ginsberg

- When Harry Met Sally (1989), at the beginning of the movie, the old couple interview, the husband mentioned that he was sitting in a Horn & Hardart cafeteria

Further reading

[edit]- Diehl, Lorraine B.; Hardart, Marianne (November 19, 2002). The Automat: The History, Recipes, and Allure of Horn & Hardart's Masterpiece. New York: Clarkson_Potter. ISBN 978-0-609-61074-9. OCLC 1298810185.[39][40][41]

- In Praise of the Automat – slideshow by Life magazine

- "The Last Automat," by James T. Farrell (New York (magazine), May 14, 1979)

- Freeland, David. "How I Love the Automat/The Place Where All the Food Is At." Life, March 22, 1928, p. 6. (Source: David Freeland, Automats, Taxi Dances and Vaudeville)

- NPR Sound Portrait: "Last Day at the Automat": Audio documentary with David Isay at the Automat on April 9. 1991

- US Expired 1199066, Fritsche, John, "Vending-machine.", published 1916-09-26, assigned to Joseph V. Horn and Frank Hardart

References

[edit]- ^ Klein, Christopher (August 23, 2018). "The Automat: Birth of a Fast Food Nation". HISTORY. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ "Futuristic 'automat' dining thrived a century ago. Can covid revive it?". Washington Post. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ "Automats". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Automat-Restaurants – Automat GmbH, 23 Spenerstrasse, Berlin, N.W. :: Trade Catalogs and Pamphlets – OCLC

- ^ "Horn & Hardart Automat, 968 6th Ave. between 35th & 36th Sts. (1986)", 36th Street, New York City Signs – 14th to 42nd Street.

- ^ "Book Reviews and Press about – The Automat – the History, Recipes, and Allure of Horn & Hardart's Masterpiece". www.theautomat.net.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (June 3, 2001). "Streetscapes/Readers' Questions; The Village Site of Eugene O'Neill's 'Iceman' Saloon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ "Joseph V. Horn, Automat Chain Co-Founder Dies," The Washington Post, October 15, 1941, p. 23.

- ^ "Smithsonian Magazine | History & Archaeology | Meet Me at the Automat". March 19, 2008. Archived from the original on March 19, 2008.

- ^ "Automat's Coffee Now Requires 2 Nickels; Two Other City Chains Ponder Dime for Cup". The New York Times. November 30, 1950. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ "Closing the Automat Door," by Peter Mikelbank, The Washington Post, September 7, 1975, p. 135.

- ^ Acquisitions, The Washington Post, August 30, 1990, pg. C2.

- ^ "Horn & Hardart to buy Royal Inn in Las Vegas for about $7.4 million". Wall Street Journal. June 20, 1979. ProQuest 134453315. (subscription required)

- ^ "Hotel's name change nearly complete (Advertising supplement)". Los Angeles Times. October 12, 1980. ProQuest 162939339. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Horn & Hardart to close hotel". New York Times. March 2, 1982. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ "Royal Americana Hotel and Casino renovated (Advertising supplement)". Los Angeles Times. March 1, 1981. ProQuest 152714896. (subscription required)

- ^ "Las Vegas also feeling sting of recession". Lawrence Journal-World. New York Times News Service. December 16, 1982. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Barron, James (April 11, 1991). "Last Automat Closes, Its Era Long Gone". The New York Times. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ "Slices of History: At New York's Last Automat only the Ambiance is the Same," by David Streitfeld, The Washington Post, April 24, 1988, p. 66.

- ^ "Food: A Taste of The Past". Time. February 8, 1988. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ^ Rubin, Daniel (December 2, 1988). "The renaissance of Horn & Hardart". Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 10-D. – Clipping at Newspapers.com.

- ^ Marter, Marilynn (August 12, 1987). "Horn & Hardart reborn". Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1-F, 12-F. – Clipping of first and of second page at Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bivens, Terry (July 6, 1987). "Gustatory Memory Is Revived Horn & Hardart Plans To Expand". Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Rubin, Daniel (December 4, 1988). "Automat Is On The Rebound". Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 25, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Michael Klein (August 8, 1994). "Horn & Hardart Foods Are Back". Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ "Horn & Hardart – Bakery Cafe". AllMenus.com. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ "Horn & Hardart Official Website". HornandHardartcoffee.com. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ "A legendary brand, REBORN". Horn & Hardart. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ^ "Why I'm Restoring Horn & Hardart". Horn & Hardart. May 26, 2023. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ Paul Auster: 4 3 2 1 Henry Holt and Company, New York 2017, e-ISBN 9781627794473, ISBN 9781627794466, p.353 chapter 3.4.

- ^ "Lunch Hour NYC". The New York Public Library. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ Crowley, Carolyn Hughes (August 1, 2001). "Meet Me at the Automat: Horn & Hardart gave big city Americans a taste of good fast food in its chrome-and-glass restaurants". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Hardart, Paul; Hardart, Tom (donors). "Horn and Hardart Records, 1921–2001". SIRIS (Smithsonian Institution Research Information System) Archives.

- ^ Schickele, Peter (1976). The Definitive Biography of P.D.Q. Bach. Random House. pp. 173–174. ISBN 0-394-46536-9.

- ^ "Hair – Colored Spade". allthelyrics.com. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ "Hair Cast Lyrics, Colored Spade lyrics". Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ "Put a Nickel In, Take Your Food Out". Wired. June 9, 2010.

- ^ 'The Automat' – a great read for those interested in convenience services, past, present and future Vending Times. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Diehl, Lorraine B.; Hardart, Marianne. "The Automat: The History, Recipes, and Allure of Horn & Hardart's Masterpiece". Catalog. Library of Congress. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

Sample text for Library of Congress control number 2001057805

- ^ Trufelman, Avery (June 4, 2019). "The Automat". 99% Invisible. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ "Nonfiction Book Review: The Automat: The History, Recipes, and Allure of Horn & Hardart's Masterpiece by Marianne Hardart, Lorraine B. Diehl". Publishers Weekly. November 1, 2002. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Horn and Hardart coffee.

- THE AUTOMAT, 2021 documentary film by Lisa Hurwitz

- Horn & Hardart Automat sign at 968 6th Avenue, Manhattan, 1986

- Used and new Automats in the United States

- 1888 establishments in Pennsylvania

- 1898 establishments in New York (state)

- 1991 disestablishments in New York (state)

- Coffee brands

- Defunct fast-food chains in the United States

- Defunct restaurant chains in the United States

- Defunct restaurants in New York City

- Defunct restaurants in Philadelphia

- Defunct restaurants in the United States

- Fast-food chains of the United States

- Regional restaurant chains in the United States

- Restaurants disestablished in 1991

- Restaurants established in 1888

- Vending