American coot

| American coot | |

|---|---|

| |

| American coot in New York City | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Rallidae |

| Genus: | Fulica |

| Species: | F. americana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Fulica americana Gmelin, JF, 1789

| |

| |

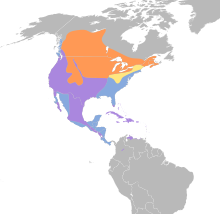

Breeding range Winter-only range Year-round range Passage

| |

| Synonyms | |

and see text | |

The American coot (Fulica americana), also known as a mud hen or pouldeau, is a bird of the family Rallidae. Though commonly mistaken for ducks, American coots are only distantly related to ducks, belonging to a separate order. Unlike the webbed feet of ducks, coots have broad, lobed scales on their lower legs and toes that fold back with each step to facilitate walking on dry land.[2] Coots live near water, typically inhabiting wetlands and open water bodies in North America. Groups of coots are called covers[3] or rafts.[2] The oldest known coot lived to be 22 years old.[2]

The American coot is a migratory bird that occupies most of North America. It lives in the Pacific and southwestern United States and Mexico year-round and occupies more northeastern regions during the summer breeding season. In the winter they can be found as far south as Panama.[2] Coots generally build floating nests and lay 8–12 eggs per clutch.[2] Females and males have similar appearances, but they can be distinguished during aggressive displays by the larger ruff (head plumage) on the male.[4] American coots eat primarily algae and other aquatic plants but also animals (both vertebrates and invertebrates) when available.[5]

The American coot is closely related to the Eurasian coot (Fulica atra), which occupies the same ecological niche in Eurasia and Australia as the American coot does in North America.[citation needed] Eurasian coots can be distinguished from this species by the absence of a red callus above the bird's frontal shield.[citation needed]

The American coot is listed as “Least Concern” under the IUCN conservation ratings.[1] Hunters generally avoid killing American coots because their meat is not as sought after as that of ducks.[2]

American coots display several interesting breeding habits; mothers will preferentially feed offspring with the brightest plume feathers, which has resulted in coot chicks having brightly ornamented plumage which becomes drabber as they age.[6][7] American coots are also susceptible to conspecific brood parasitism and have evolved mechanisms to differentiate their offspring from those of parasitic females.[8]

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]

The American coot was formally described in 1789 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it with all the other coots in the genus Fulica and coined the binomial name Fulica americana.[9] Gmelin based his description on the "Cinereous coot" from North America that had been described in 1785 by the English ornithologist John Latham in his book A General Synopsis of Birds.[10]

Subspecies

[edit]Two subspecies are recognised:[11]

- F. a. americana Gmelin, JF, 1789 – southeast Alaska and Canada to Costa Rica and the West Indies

- F. a. columbiana Chapman, 1914 – Colombia and north Ecuador

The Caribbean coot, a color morph of the American coot is now included with the nominate subspecies.[11][12]

Fossil record

[edit]Coot fossils from the Middle Pleistocene of California have been described as Fulica hesterna but cannot be separated from the present-day American coot.[13] However, the Pleistocene coot Fulica shufeldti (formerly F. minor), famously known as part of the Fossil Lake fauna, quite possibly was a paleosubspecies of the American coot (as Fulica americana shufeldti) as they only differed marginally in size and proportions from living birds.[14] Thus, it seems that the modern-type American coots evolved during the mid-late Pleistocene, a few hundred thousand years ago.[13][14]

The American coot's genus name, Fulica, is a direct borrowing of the Latin word for "coot".[15] The specific epithet americana means "America".[16]

Description

[edit]

The American coot measures 34–43 cm (13–17 in) in length with a wingspan of 58 to 71 cm (23 to 28 in). Adults have a short, thick, white bill and white frontal shield, which usually has a reddish-brown spot near the top of the bill between the eyes. Males and females look alike, but females are smaller. Body mass in females ranges from 427 to 628 g (0.941 to 1.385 lb) and in males from 576 to 848 g (1.270 to 1.870 lb).[17][18][19] Juvenile birds have olive-brown crowns and a gray body. They become adult-colored around 4 months of age.[5]

Frontal shield and callus

[edit]This subsection includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2024) |

The American coot is recognized by its white frontal shield with a red spot connecting its eyes. The size of the frontal shield depends on season and mating status. During the winter season, birds have smaller, 'shrunken' shields. During breeding season, birds are recorded to have swelled shields. Birds that are permanently paired or mated have larger shields as well.

According to a 1949 coverage by Gordon W. Gullion, the reddish-brown spot on the frontal shield is not considered a part of the frontal shield despite its proximity to the shield. It is known as the callus. This is due to the fact that it does not completely cover the maxilla, or jawbone, of the coot. It also differs in color and texture from the shield.

Vocalizations

[edit]The American coot has a variety of repeated calls and sounds. Male and female coots make different types of calls to similar situations. Male alarm calls are puhlk while female alarm calls are poonk. Also, stressed males go puhk-cowah or pow-ur while females call cooah.[5]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

American coots are found near water reed-ringed lakes and ponds, open marshes, and sluggish rivers. They prefer freshwater environments but may temporarily live in saltwater environments during the winter months.[5]

The American coot's breeding habitat extends from marshes in southern Quebec to the Pacific coast of North America and as far south as northern South America. Birds from temperate North America east of the Rocky Mountains migrate to the southern United States and southern British Columbia. It is often a year-round resident where water remains open in winter. The number of birds that stay year-round near the northern limit of the species' range seems to be increasing.[20][21]

Autumn migration occurs from August to December, with males and non-breeders moving south before the females and juveniles. Spring migration to breeding ranges occurs from late February to mid-May, with males and older birds moving North first. There has been evidence of birds travelling as far north as Greenland and Iceland.[5]

Caribbean coot

[edit]

Coots resident in the Caribbean and Greater and Lesser Antilles lack the red portion of the frontal shield, and were previously believed to be a distinct species, the Caribbean coot (Fulica caribaea). In 2016, due to research showing that the only distinguishing characteristic between American and Caribbean coots, the presence or absence of red in the frontal shield, was not distinct to Caribbean coots as some American coots, in locations where vagrancy from Caribbean populations was highly unlikely, had fully white shields and, therefore, there was no way to reliably distinguish the species, and there was no evidence of Caribbean and American coots engaging in assortative mating,[22] the American Ornithological Society lumped the Caribbean coot as a regional variation of the American coot.[23][24]

Behavior and ecology

[edit]The American coot is a highly gregarious species, particularly in the winter, when its flocks can number in the thousands.[25] When swimming on the water surface, American coots exhibit a variety of interesting collective formations, including single-file lines, high density synchronized swimming and rotational dynamics, broad arcing formations, and sequential take-off dynamics.[26]

Feeding

[edit]The American coot can dive for food but can also forage and scavenge on land. Their principal source of food is aquatic vegetation, especially algae. Yet they are omnivorous, also eating arthropods, fish, and other aquatic animals. During breeding season, coots are more likely to eat aquatic insects and mollusks—which constitute the majority of a chick's diet.[5]

-

Foraging

-

Eating a worm

-

Eating algae

-

With fish

Breeding

[edit]

The coot mating season occurs during May and June.[27] Coot mate pairings are monogamous throughout their life, given they have a suitable territory. A typical reproductive cycle involves multiple stages: pairing, nesting, copulation, egg deposition, incubation, and hatching.[28] The American coot typically has long courtship periods. This courtship period is characterized by billing, bowing, and nibbling. Males generally initiate billing, which is the touching of bills between individuals. As the pair bond becomes more evident, both males and females will initiate billing only with each other and not other males or females. After a pair bond is cemented, the mating pair looks for a territory to build a nest in. A pair bond becomes permanent when a nesting territory is secured. Copulation behavior among coot pairs always falls under the same general pattern.[28] First the male chases the female. Then, the female moves to the display platform and squats with her head under the water. The male then mounts the female, using his claws and wings to balance on the female's back while she brings her head above the water. Sexual intercourse usually takes no longer than two seconds.[28]

Nests

[edit]The American coot is a prolific builder and will create multiple structures during a single breeding season. It nests in well-concealed locations in tall reeds. There are three general types of structures: display platforms, egg nests and brood nests.

- Display platforms are used as roosting sites and are left to decompose after copulation.

- Egg nests are typically 30 cm (12 in) in diameter with a 30–38 cm (12–15 in) ramp that allows the parents to enter and exit without tearing the sides of the nests. Coots will often build multiple egg nests before selecting one to lay their eggs in.

- Brood nests are nests that are either newly constructed or have been converted from old egg nests after the eggs hatch, becoming larger egg nests.

Since American coots build on the water, their structures disintegrate easily and have short life spans. Egg and brood nests are actually elaborate rafts, and must be constantly added to in order to stay afloat. Females typically do the most work while building.[28]

Egg-laying and clutch size

[edit]Females deposit one egg a day until the clutch is complete. Eggs are usually deposited between sunset and midnight. Typically, early season and first clutches average two more eggs than second nestings and late season clutches. Early season nests see an average of 9.0 eggs per clutch while late clutches see an average of 6.4 eggs per clutch. There is an inverse relationship between egg weights and laying sequence,[29] wherein earlier eggs are larger than eggs laid later in the sequence. It is possible to induce a female coot to lay more eggs than normal by either removing all or part of her clutch. Sometimes, a female may abandon the clutch if enough eggs are removed. Coots, however, do not respond to experimental addition of eggs by laying fewer eggs.[30]

The American coot is a persistent re-nester, and will replace lost clutches with new ones within two days of clutch-loss during deposition. One study showed that 68% of destroyed clutches are eventually replaced. Re-nested clutches are typically smaller than original clutches by one or two eggs, but this could be attributed to differences in time and habitat quality instead of food or nutrient reserves and availability.[31]

Younger females reproduce later in the season and produce smaller eggs than older females. Their offspring are also smaller. However, there is no difference in clutch size between older and younger females as there is in other avian species.[32]

Incubation and hatching

[edit]Incubation start time in the American coot is variable, and can begin anywhere from the deposition of the first egg to after the clutch is fully deposited. Starting incubation before the entire clutch has been laid is an uncommon practice among birds.[33] Once incubation starts it continues without interruption. Male and female coots share incubation responsibility, but males do most of the work during the 21-day incubation period. Females will begin to re-nest clutches in an average of six days if clutches are destroyed during incubation.[31]

Hatch order usually follows the same sequence as laying order. Regardless of clutch size, eight is the typical maximum size of a brood. Egg desertion is a frequent occurrence among coots because females will often deposit more than eight eggs. Brood size limits incubation time, and when a certain number of chicks have hatched the remaining eggs are abandoned. The mechanism for egg abandonment has not yet been discovered. Food resource constraints may limit the number of eggs parents let hatch, or the remaining eggs may not provide enough visual or tactile stimulation to elicit incubation behavior.[33] An American coot can be forced to hatch more eggs than are normally laid. These additional offspring, however, suffer higher mortality rates due to inadequacy in brooding or feeding ability.[34]

Maternal effects

[edit]Hormones that are passed down from the mother into the egg affect offspring growth, behavior, and social interactions. These nongenetic contributions by the mother are known as maternal effects. In the American coot, two levels of androgen and testosterone variation have been discovered—within-clutch and among-clutch variation. Within the same clutch, eggs laid earlier in the sequence have higher testosterone levels than eggs laid later in the sequence. Females that lay three clutches deposit more androgens into their yolks than females who lay only one or two clutches.[35]

Brood parasitism

[edit]The American coot has a mixed reproductive strategy, and conspecific brood parasitism is a common alternative reproductive method. In one 4-year study, researchers found that 40% of nests were parasitized, and that 13% of all eggs were laid by females in nests that were not their own.[36] Increasing reproductive success under social and ecological constraints is the primary reason for brood parasitism. Floater females without territories or nests use brood parasitism as their primary method of reproduction, if they breed at all. Other females may engage in brood parasitism if their partially complete clutches are destroyed. Conspecific brood parasitic behavior is most common among females trying to increase their total number of offspring. Food supply is the limiting factor to chick survival and starvation is the most common cause of chick morbidity. Parasitic females bypass the parental care constraint of feeding by laying additional parasitic eggs in addition to their normal nest.[36]

When a parasitic female lays her egg in a host female's nest, the host female experiences a deposition rate of two eggs per day. Host females may recognize parasitic eggs when the egg deposition pattern deviates from the traditional one egg per day pattern.[30] The occurrence of brood parasitism may be influenced by the body size of the potential parasitic female relative to the potential host female. Parasitic females are generally larger than their host counterparts, but on average, there is no size difference between the parasite and the host.[37]

The American coot, unlike other parasitized species, has the ability to recognize and reject conspecific parasitic chicks from their brood.[8] Parents aggressively reject parasite chicks by pecking them vigorously, drowning them, preventing them from entering the nest, etc. They learn to recognize their own chicks by imprinting on cues from the first chick that hatches. The first-hatched chick is a reference to which parents discriminate between later-hatched chicks. Chicks that do not match the imprinted cues are then recognized as parasite chicks and are rejected.[8]

Chick recognition reduces the costs associated with parasitism, and coots are one of only three bird species in which this behavior has evolved. This is because hatching order is predictable in parasitized coots—host eggs will reliably hatch before parasite eggs. In other species where hatching order is not as reliable, there is a risk of misimprinting on a parasite chick first and then rejecting their own chicks. In these species, the cost of accidentally misimprinting is greater than the benefits of rejecting parasite chicks.[8]

Chick ornaments

[edit]The first evidence for parental selection of exaggerated, ornamental traits in offspring was found in American coots.[38] Black American coot chicks have conspicuously orange-tipped ornamental plumes covering the front half of their body that are known as “chick ornaments” that eventually get bleached out after six days. This brightly colored, exaggerated trait makes coot chicks more susceptible to predation and does not aid in thermoregulation, but remains selected for by parental choice. These plumes are not necessary for chick viability, but increased chick ornamentation increases the likelihood that a chick will be chosen as a favorite by the parents. Experimental manipulation of chick ornamentation by clipping the bright plumes has shown that parents prefer ornamented chicks over non-ornamented ones.[38]

- Growth series

-

Young chicks

-

Older chicks

-

Young juvenile

-

Older juvenile

-

Adult

Predation

[edit]The American coot is fairly aggressive in defense of its eggs and, in combination with their protected nesting habitat, undoubtedly helps reduce losses of eggs and young to all but the most determined and effective predators. American crows, black-billed magpies and Forster's tern can sometimes take eggs. Mammalian predators (including red foxes, coyotes, skunks and raccoons) are even less likely to predate coot nests, though nests are regularly destroyed in usurpation by muskrats. Conversely, the bold behavior of immature and adult coots leads to them falling prey with relative regularity once out of the breeding season. Regular, non-nesting-season predators include great horned owls, northern harriers, bald eagles, golden eagles, American alligators, bobcats, great black-backed and California gulls. In fact, coots may locally comprise more than 80% of the bald eagle diet.[39]

In culture

[edit]

On the Louisiana coast, the Cajun word for coot is pouldeau, from French for "coot", poule d'eau – literally "water hen". Coot can be used for cooking; it is somewhat popular in Cajun cuisine, for instance as an ingredient for gumbos cooked at home by duck hunters.[40] The bird is the mascot of the Toledo Mud Hens Minor League Baseball team.[41]

Conservation and threats

[edit]The American coot is listed under "least concern" by the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. They are common and widespread, and are sometimes even considered a pest. They are rarely the targets of hunters since their meat is not considered to be as good as that of ducks; although some are shot for sport, particularly in the southeastern United States. Because they are found in wetlands, scientists use them to monitor toxin levels and pollution problems in these environments.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International. (2016). "Fulica americana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T62169677A95190980. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T62169677A95190980.en.

- ^ a b c d e f g "American Coot". allaboutbirds.org.

- ^ Group Names for Birds, Baltimore Bird Club

- ^ Gullion, Gordon W. (1952). "The Displays and Calls of the American Coot". The Wilson Bulletin. 64 (2): 83–97. JSTOR 4158081.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoyo, Josep del (1996). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-8487334207.

- ^ Stephens, Tim (30 December 2019). "The mysterious case of the ornamented coot chicks has a surprising explanation". UC Santa Cruz.

- ^ Davies, Nicholas B.; Krebs, John R.; West, Stuart A. (2012). "8". Behavioural Ecology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9781405114165.

- ^ a b c d Shizuka, Daizaburo; Lyon, Bruce E. (16 December 2009). "Coots use hatch order to recognize and reject conspecific brood parasitic chicks". Nature. 463 (7278): 223–226. doi:10.1038/nature08655. PMID 20016486. S2CID 4161373.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 704.

- ^ Latham, John (1785). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 3, Part 1. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. p. 279.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Flufftails, finfoots, rails, trumpeters, cranes, limpkin". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ Chesser, R. Terry; Burns, Kevin J.; Cicero, Carla; Dunn, John L.; Kratter, Andrew W; Lovette, Irby J; Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Remsen, J.V. Jr; Rising, James D.; Stotz, Douglas F.; Winker, Kevin (2017). "Fifty-seventh supplement to the American Ornithological Society's Check-list of North American Birds". The Auk. 133 (3): 544–560. doi:10.1642/AUK-16-77.1.

- ^ a b Olson, Storrs L. (1974). "The Pleistocene Rails of North America". Museum of Natural History.

- ^ a b Jehl, Joseph R. (1967). "Pleistocene Birds from Fossil Lake, Oregon". The Condor. 69 (1): 24–27. doi:10.2307/1366369. JSTOR 1366369.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2009). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishers. pp. 165. ISBN 978-1408125014.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2009). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishers. pp. 44. ISBN 978-1408125014.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ "American Coot". Arkive. Archived from the original on 2013-11-19. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ American Coot – Fulica americana. oiseaux-birds.com

- ^ Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A Preliminary List of Birds in Seneca County, Ohio". The Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60. JSTOR 4154076.

- ^ "American Coot" (PDF). Ohio Ornithological Society. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ Retter, Michael (July 7, 2016). "2016 AOU Supplement is Out!". American Birding Association. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ^ Nicholson, Paul (August 3, 2016). "The World Outdoors: Climate change shifting bird ranges". The London Free Press. London, Ontario. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ^ "Clements Checklist: Updates & Corrections – August 2016". Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. August 9, 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ^ Dunne, Pete (2006). Pete Dunne's Essential Field Companion. New York, NY, USA: Houghton, Mifflin. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-618-23648-0.

- ^ Trenchard, Hugh (2013). "American coot collective on-water dynamics". Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences. 17 (2): 183–203. PMID 23517605.

- ^ Bridgman, Allison; Rudi Berkelhamer. "American Coot". BioKids. University of Michigan. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d Gullion, Gordon (October 1954). "Reproductive Cycle in American Coots". Auk. 71 (4): 366–412. doi:10.2307/4081536. JSTOR 4081536.

- ^ Alisauskas, Ray T. (Feb 1986). "Variation in the Composition of the Eggs and Chicks of American Coots". The Condor. 88 (1): 84–90. doi:10.2307/1367757. JSTOR 1367757.

- ^ a b Arnold, Todd W. (July 1992). "Continuous Laying by American Coots in Response to Partial Clutch Removal and Total Clutch Loss". The Auk. 3. 109 (3): 407–421. JSTOR 4088356.

- ^ a b Arnold, Todd W. (May 1993). "Factors Affecting Renesting in American Coots". The Condor. 95 (2): 273–281. doi:10.2307/1369349. JSTOR 1369349.

- ^ Crawford, Richard D. (Jan 1980). "Effects of Age on Reproduction in American Coots". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 1. 44 (1): 183–189. doi:10.2307/3808364. JSTOR 3808364.

- ^ a b Fredrickson, Leigh H. (July 1969). "An Experimental Study of Clutch Size of the American Coo". The Auk. 3. 86 (3): 541–550. doi:10.2307/4083414. JSTOR 4083414.

- ^ Ryan, Mark R.; James J. Dinsmore (May 1979). "A Quantitative Study of the Behavior of Breeding American Coots" (PDF). The Auk. 96: 704–713.

- ^ Reed, Wendy L.; Carol M. Vleck (March 2001). "Functional significance of variation in egg-yolk androgens in the American coot" (PDF). Oecologia. 128 (2): 164–171. Bibcode:2001Oecol.128..164R. doi:10.1007/s004420100642. PMID 28547464. S2CID 2798198. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ^ a b Lyon, Bruce; et al. (October 1992). "Conspecfic brood parasitism as a flexible female reproductive tactic in American coots" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 46 (5): 911–928. doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1273. S2CID 53188986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- ^ Lyon, Bruce; et al. (2003). "Ecological and social constraints on conspecific brood parasitism by nesting female American coots (Fulica americana)". Journal of Animal Ecology. 72 (1): 47–61. Bibcode:2003JAnEc..72...47L. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00674.x.

- ^ a b Lyon, Bruce; et al. (September 1994). "Parental choice selects for ornamental plumage in American Coot chicks". Nature. 371 (6494): 240–242. Bibcode:1994Natur.371..240L. doi:10.1038/371240a0. S2CID 4239627.

- ^ Brisbin Jr., I. Lehr; Mowbray, Thomas B.; Poole, A.; Gill, F. (2002). Poole, A; Gill, F (eds.). "American Coot (Fulica americana)". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.697a.

- ^ Horst, Gerald. "Chuck Buckley's Duck (Coot) Gumbo". Louisiana Sportsman. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Toledo Mudhens". Minor League Baseball. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

Cited sources

[edit]- Jobling, James A. (2009). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, UK: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

External links

[edit]- American Coot – Fulica americana – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter.

- American Coot Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- "American Coot media". Internet Bird Collection.

- American Coot photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)